The village of Zababdeh in the northern occupied West Bank, which is 70 percent Christian, is home to a young and vibrant community that has been hit hard by the consequences of the war.

By Cécile Lemoine

It is time for communion and, in the small Greek Orthodox church of Zababdeh, it is the ballet of the mantillas. Like women and other young girls, Rafeef Duaibes piously covers her hair with a lace veil before going to communion. Abandoned by most Christians in the cities, this tradition has remained firmly rooted in Zababdeh, a small town in the fertile plains of the northern occupied West Bank.

It's Sunday, and the pews of the church are overflowing. The young Rafeef has joined her classmates. There are grandfathers with well-groomed mustaches, young parents who have come to present their babies to the church for the first time, friends who are quietly having fun upstairs, young women who chat outside, toddlers who frolic... A time of socialization as much as of prayer, Zababdeh's Sunday Masses are a reflection of the vitality of its Christian community. And of it’s a-typical character.

Things happen differently in Zababdeh. With 3,500 Christians out of a population of 5,000, it is the only village with a Christian majority in the north of the occupied West Bank. It is also one of the few communities in Palestine where Latin rite Christians are more numerous than those of the Greek rite (2,500 Latins, compared with 800 Greek Orthodox and 50 Greek Catholics). A Protestant church of 135 faithful completes the picture. Another difference is the size of the families. While Christians have an average of 2 children, in Zababdeh it is common to find families of 6, 7 or 8 children. The Duaibes are one of them. Rafeef has 3 older brothers and 3 older sisters. And this entire group lives in the same house: an enlarged old building where each floor is supposed to accommodate the families founded by the boys. For them, as in many Palestinian homes, family is the cardinal bond.

A Bustling Community

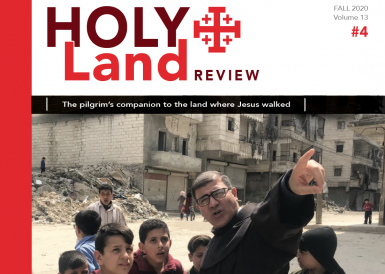

This sociological particularity makes Zababdeh the beating heart of Palestinian Christians: "We have the largest scout group in the country, Israel and Palestine combined," says Father Elias Tabban, parish priest of the Latin parish. With their 370 members, their grey uniforms and purple berets, Zababdeh's scouts rarely go unnoticed during Christmas parades in Bethlehem. If they are not scouts, the teenagers of the village are part of the "shabibe", these groups of young Christians equivalent to the Young Christian Students movement.

"The priests like to be appointed here, the churches are full of life," smiles Issa, the second of the Duaibes siblings. "It's an anthill here, it's hyperactive," says Father Elias, who only joined the parish in 2023: "You have to see how full the churches are at Easter and Christmas. Those who live or work in Bethlehem, Ramallah, Taybeh, come back for the holidays... It overflows!" And how does he explain this swarming? "Here, the Church is the center of life. For many, it's the only stable thing they have left, that keeps them going, so they get involved."

The parish is a place of prayer as much as a place of flourishing community social life.

Growing up in Zababdeh means growing up under military occupation. And since October 7, that means the people have seen their life reduced to their city and its immediate surroundings. Checkpoints, barriers, mounds of earth – nearly 900 obstacles impede the movement of Palestinians and isolate cities from each other. The Latin parish counts 300 men who have lost their jobs in Israel, and their incomes. The youngest are struggling to find work. "There is no future here," says Yacoub, a 21-year-old friend of Issa's. Trained in electrical engineering, he only found a small job in village's Latin school’s cafeteria.

Israeli settlers have plastered this phrase – "There is no future in Palestine" – it on large billboards along West Bank roads, or on the concrete blocks that serve as watchtowers for soldiers. It soaks into and torments minds already tortured by a daily life of humiliation and violence. "What kind of life are we giving our children?" asks Majeed, the eldest of the Duaibes family, married and the father of a little girl. "If there was an opportunity to go abroad, I would take it." To dispel boredom and worries, this dentist opened a small café, the Solo Caffe. In the evening, the boys of the village, Christians and Muslims alike, meet there, amidst the thick steam of hookahs, for games of cards, billiards, or video games with friends. Here, they find a family they have chosen for themselves. One that helps them disconnect from social networks, where videos of the massacres in Gaza run in a loop. The fear of being next replaces the feeling of powerlessness. "All we have left is prayer," said Daoud Daoud, a young Greek Orthodox deacon, at the end of the mass. In the harshness of this daily life, some find refuge in faith and expect greater pastoral and spiritual accompaniment from the priests: "We have to be churches," Wassim, father of two children and active member of the Latin parish, says with emotion. “Sion is in our hearts, we can continue to take the situation, to keep this link to the earth."

Solidarity with Displaced Palestinians

While Zababdeh remains relatively spared from military raids, it is feeling the consequences. Around 40,000 people have been evacuated from the surrounding refugee camps since January 2025, the largest displacement since 1967. Nearly 200 families from the Jenin camp have found refuge in Zababdeh, including on the campus of the American University, without knowing when they will be able to return home. Faced with the scale of the phenomenon, the Church has mobilized, through the NGO Caritas, which is already active in the region. "With the help of two parishioners, we are in the process of carrying out a census of families, to find out what their needs are," explains Anton Asfar, director of Caritas Jerusalem. The idea is to provide them with financial assistance ranging from 500 to 1,600 shekels (€120 to €380). It's the most dignified way to concretely help these people who have lost everything." In Zababdeh, Christians approve of this aid but express their concern about the future: "If these families stay, in the long term, it could change the demographic balance of the town: Muslims could become the majority," says Jumana Daoud, a Christian member of the village council."

Blessing of newborns entering the church for the first time, according to the Greek Orthodox rite.

Faced with the challenges that are piling up, the Latin priest is convinced: "The Christians of Zababdeh must be strengthened. Without them, the churches are empty. Here, Christians are not weak, the parish priest continues. They love the land. They prefer to stay rather than to leave. I say to the Patriarch: in the future, if you need people, you will find them in Zababdeh."

Terre Sainte Magazine, #697, May 2025